The Vancouver Island Railway, originally known as the Esquimalt & Nanaimo (E&N) Railway, was founded on September 27, 1883, by Victoria coal magnate Sir Robert Dunsmuir. It was built to support the burgeoning local coal and timber industries, and also to serve the Royal Naval Base in Esquimalt. Learn more at vancouver-future.

Building the Vancouver Island Railway

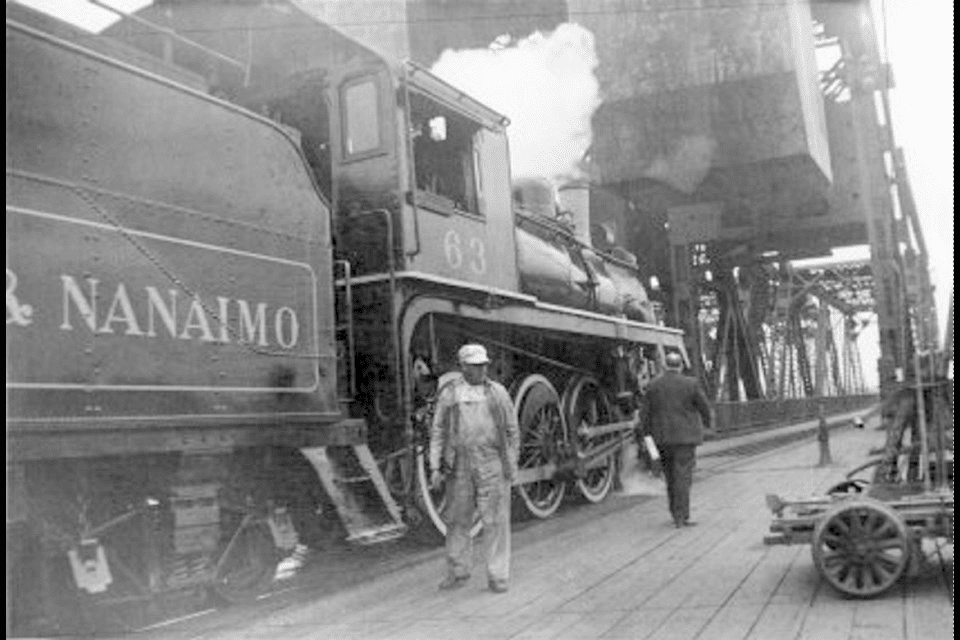

Construction began on April 30, 1884. Just over two years later, on August 13, 1886, Canadian Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald ceremoniously drove the last spike into the section of railway crossing the Malahat Highway. The initial 115-kilometre route stretched from Esquimalt to Nanaimo, giving the company its original name. In 1888, the line was extended to Victoria. The railway was intended to be part of the agreement for British Columbia’s entry into the Canadian Confederation, and while the project was never fully completed as envisioned, it was still considered a vital component of the national Trans-Canada railway system.

In 1905, James Dunsmuir, the founder’s son, sold the E&N to Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). CPR expanded the network to Cowichan Lake, Port Alberni, Parksville, Qualicum Beach, and Courtenay. At its peak, the railway served 45 stations on the main line, 8 on the Port Alberni branch, and another 36 on the Cowichan branch. Today, roughly 25 stations remain, though most are no longer operational and are slowly deteriorating.

In 1953, CPR discontinued passenger service to Port Alberni. Later, in 1979, VIA Rail took over passenger operations, while CPR maintained ownership of the railway itself. VIA provided the cars, covered the costs of passenger transport, and managed ticket sales. However, due to a lack of promotion, the route remained largely isolated, not fully integrated into Canada’s or North America’s broader transportation network.

1990s Crisis and the Search for Solutions

In 1998, CPR transferred the east-west branch between Parksville and Port Alberni to Rail America. Simultaneously, a freight agreement was made to transport goods to the barge terminal in Nanaimo. At the time, approximately 8,500 carloads of forestry products, minerals, and chemicals were transported annually. Changes accelerated after Norske, a company owning several pulp and paper mills in Port Alberni, opted for truck transportation over rail. With the loss of this key client, Rail America announced plans to cease operations and exit Vancouver Island.

The Vancouver Island Railway operated under unstable conditions for a long time. CPR failed to provide adequate maintenance, and the general decline of the railway industry across North America only exacerbated this trend. The number of freight clients dwindled, and this part of the Trans-Canada railway system gradually lost its significance. Meanwhile, local residents actively advocated for the preservation of rail service. Many community initiatives tried to reach out to responsible bodies to improve the situation, but the decline continued. When Rail America announced the cessation of passenger and freight services, island communities reacted with outrage. In response, two major conferences were organized – a last-ditch effort to change the situation before it reached a critical point.

A series of roundtables, aptly named “The Future of the Vancouver Island Railway,” brought together all stakeholders. Some joined reluctantly, but they joined nonetheless. These meetings became not only a search for a way out of the crisis but also a platform for lively discussion and collaboration. At that time, passenger service and some freight operations were still clinging on, barely.

Establishing the Island Corridor Foundation

Thanks to the initiative of Vancouver Island residents, who joined forces with local governments and First Nations, the Island Corridor Foundation (ICF) was established in 2003. This non-profit organization, created under Part II of the Canada Corporations Act, received charitable status under the Income Tax Act in December 2004. Its members included regional districts and First Nations communities located along the former railway corridor, who became the fund’s founders. Leveraging its status, the ICF negotiated with CPR to acquire ownership of the railway lands in exchange for a tax receipt, which the foundation could officially issue. In parallel, negotiations with Rail America resulted in the return of that section of the line. This, in turn, allowed for the consolidation of the infrastructure into a single island railway system.

Overall, the ICF’s vision was to preserve this railway corridor forever as a single route connecting island residents and fostering local development, particularly for First Nations. The foundation’s mission was to expand the corridor’s functionality, integrate it with other transportation systems, and establish cooperation with an operator who would develop passenger, freight, and commuter services.

The Path to Revival

The railway lands span 651 hectares (1610 acres). The track stretches 234 kilometres (139 miles) from Victoria to Courtenay, encompassing 13 First Nations territories, 14 municipalities within five regional districts, and several smaller unincorporated communities. In 2006, the Foundation found a reliable operator: Southern Rail Ltd. of Vancouver Island. Despite challenging conditions, they took on both freight and passenger services. What’s more, they opened the island to a full rail connection with the mainland by building a new barge terminal on the coast, through which goods arrive at Nanaimo port. The company continues to operate on the island, confident in the Vancouver Island Railway’s potential and equipped with a well-justified business plan.

The ICF, supported by local communities and individuals, continues to work diligently on developing a robust business plan. The goal is to convince the federal and provincial governments of the importance of funding infrastructure, which would pave the way for the restoration of a successful railway system. This strategy bore fruit in the summer of 2011, when the Province of British Columbia allocated $7.5 million to the project. Half a million was earmarked for studying the condition of bridges and viaducts, some of which had stood for over 125 years. The research confirmed that most structures remained sound, ensuring the railway’s continued operational viability. In April 2012, the federal government reciprocated, providing funding during a celebratory ceremony in Langford. The city’s mayor declared, “This is the day the Vancouver Island Railway was saved!”

So, what’s happening now? The story continues to unfold: rail service is being restored, passenger operations are returning, and freight volumes are gradually increasing thanks to Southern Rail’s efforts. There’s still plenty of work ahead, but Vancouver Island residents are confident that this railway is a long-term prospect.