Vancouver’s beginnings weren’t just about railways, sawmills, and pubs; they were also about brothels, which over the years formed their own distinct urban structure. This line of work developed alongside the industrial boom, meeting the demand within the working-class environment. In response to public pressure, the authorities didn’t ban prostitution outright but instead gradually designated a place for it on the city map. This is how red-light districts formed—officially unrecognized, yet clearly localized. More at vancouver-future.

One of the most famous of these areas was Alexander Street. It was here that a brothel appeared in 1912, built specifically for a Madam Alice Bernard. This house was not just a residence but an architecturally designed place of work, comfort, and profit. Read on to learn why this building came to be, who founded it, and what happened behind its doors.

The Red-Light District and the Rise of Alexander Street

In the early 20th century, Vancouver was developing rapidly. With the construction of the railway, the expansion of the port, and a growing number of newcomers, the city needed not only housing and infrastructure but also areas where activities that were officially forbidden could be permitted. Prostitution was one such sphere. Brothels operated in a semi-legal gray area in several districts, including Shore Street. However, the authorities, responding to public pressure and wanting to reduce the chaos, decided to concentrate this activity in a designated district.

Thus, in 1912, the red-light district on Alexander Street emerged, a street located near the port and the railway. The choice was logical: the lots here were inexpensive, the area was conveniently located, and the residents didn’t protest. Most importantly, the zone was set apart from the main residential neighbourhoods, which helped to avoid scandals. For the first time in the city’s history, the brothels here weren’t just converted residential homes but were built from the ground up—as distinct architectural objects specifically designed for this function. City council approved several permits for the construction of rooming houses on Alexander Street, which were effectively brothels. The clients who commissioned them were well-known women, among them Madam Alice Bernard. Her building at 514 Alexander Street became one of the most famous and expensive: the estimated cost was $14,500—a sum that indicated the high ambitions and expected profitability of the future establishment. The architecture of the buildings in this zone was distinguished by its thoughtful planning: numerous rooms, spacious living areas, separate entrances, and elements meant to emphasize respectability.

This is how a small but orderly red-light district was formed, with a dozen buildings that became part of the urban landscape. For several years, Alexander Street gained a reputation as a place where prostitution was, so to speak, controlled. But this order would soon be disrupted.

Who Was Madam Alice Bernard and How Did Her Brothel Come to Be?

In 1912, as the city of Vancouver was actively forming its new red-light district on Alexander Street, among those who received a permit to build a brothel was the formidable Madam Alice Bernard. She was no random figure; she was known in the city as an experienced organizer and one of the few women who openly managed such a business. Little is known about her origins, but archival sources indicate that by the time of the construction, she already had experience running similar establishments, likely in other parts of the city.

Unlike other brothels, which were often housed in converted residential buildings, Madam Bernard decided to construct a purpose-built structure, taking into account functional needs and a long-term vision. She obtained all permits officially, and on city maps, her project was listed as a rooming house, which allowed the business to operate legally. However, Alice didn’t just invest in real estate—she created a space where sex workers had safe conditions to work, and clients had a predictable, controlled atmosphere. Her establishment became one of the most famous in the district, not because of scandals, but due to its orderliness and reputation. Madam Bernard herself personifies an era when women, facing social marginalization, created their own rules, particularly within the urban environment.

The Brothel’s Architecture and Functionality

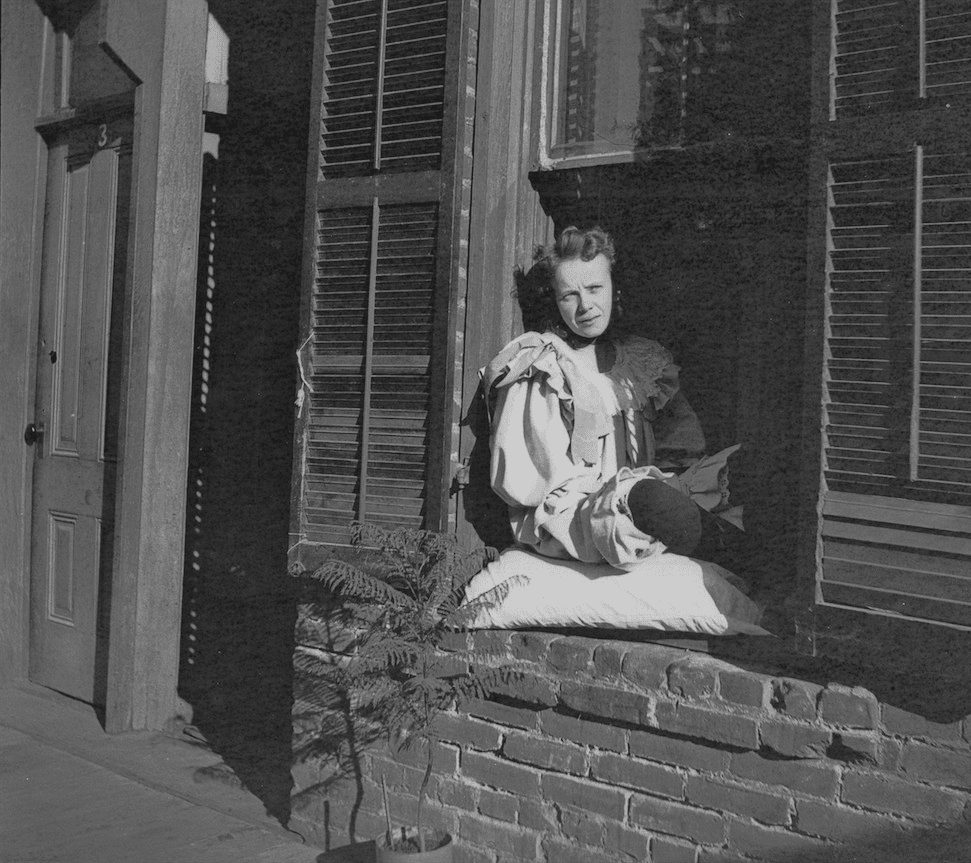

Madam Bernard’s building became one of the most famous examples of how a space could be adapted to the needs of the sex trade. The three-storey, wood-frame house with its symmetrical facade, multiple entrances, balconies, and wide porch did not look like a typical brothel. Outwardly, it could have passed for a boarding house or a private hotel, which was part of the strategy—to remain visually neutral but functionally effective. The layout had a clear structure: the ground floor contained a living room, administrative rooms, and a kitchen. The second floor was the main work area, where clients were received in separate rooms. The third floor was used as living quarters for the workers. Each room had separate lighting, and some had individual entrances or additional interior doors. All the rooms were soundproofed, and there was a clear division between the zones. This spatial hierarchy helped to avoid conflicts and ensure control.

Architecturally, the house combined functionality with stylistic elements typical of the middle class of that era: decorative trim, wood finishes, and the proper geometric lines of the facade. It maintained a balance between modesty and orderliness, creating a space that was simultaneously inconspicuous and professional. Thus, this was not an underground brothel but an organized establishment with a well-thought-out plan, and that made it stand out. Although the brothel ceased operations in 1914, the building itself has been preserved. Today, it serves a residential function, yet its architecture still bears the features of its original purpose.

Daily Life, Interior, Clients, and Public Perception

Madam Alice Bernard’s brothel was an organized space with a clear system of operation. The interior differed from ordinary houses—the client rooms were furnished for comfort and privacy. Curtains, furniture, and lighting were used to create a discreet but pleasant atmosphere. The women who worked there lived on the top floor, which was separate from the client areas. The management strictly controlled order and safety, which helped maintain the establishment’s reputation.

Clients were varied—from ordinary locals to businessmen and travellers. The brothel was respected for its organization and safety, yet public attitudes toward it and its inhabitants were still mixed. Although such establishments officially existed and paid taxes, they remained on the margins in the eyes of the general population. Meanwhile, the authorities even conducted raids, even though Madam Bernard was noted as one of Vancouver’s most organized proprietors.

In 1914, Vancouver’s policy on prostitution changed. Official brothels were banned, and the red-light district began to gradually disappear. Madam Alice Bernard’s brothel ceased its operations, but the building on Alexander Street remained. Today, this house is considered a historic landmark that serves as a reminder of a complex and ambiguous chapter in Vancouver’s urban development. Its heritage status allows for the preservation of the unique architectural features of the early 20th century and to honour the legacy associated with one of the city’s most famous brothels.