Among the stately mansions that have weathered countless eras, Hycroft Manor in Vancouver holds a special place. It has been a private residence, a military hospital, and a cultural hub for women scholars. But behind its columned facade and meticulously manicured terraces lies more than just a beautiful building. It’s a space that holds the stories of people, events, and changes that have shaped not only a single structure but also a significant part of the city. Read more on vancouver-future.

How Hycroft Manor Came to Be

In the early 20th century, Vancouver was still finding its modern identity. Cobblestone streets, trees replacing fences, and rapid commercial development were quickly pushing out wooden houses. It was during this period, in 1909, that a mansion began to rise in the elite Shaughnessy neighbourhood. This future residence would be named Hycroft Manor. General Alexander Duncan, the estate’s patron, had a brilliant military career, extensive business connections, and a clear vision for what a true home should be. It wasn’t just meant to be a dwelling, but a place for entertaining, official visits, and showcasing the building’s status. So, comfort wasn’t the top priority. Duncan wanted a space that would impress at first glance. And Hycroft certainly delivered: not monumental, but meticulously detailed, almost theatrically impactful.

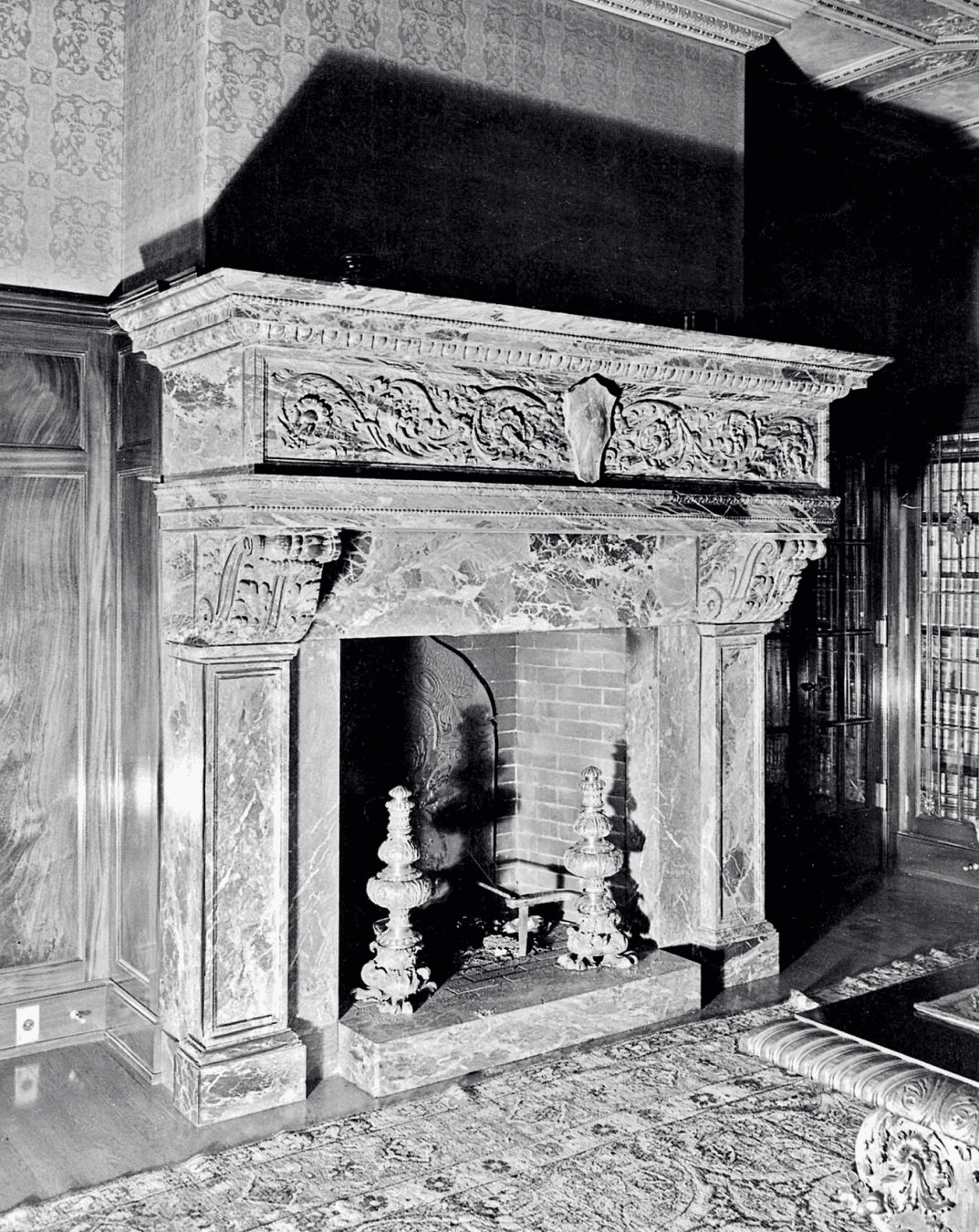

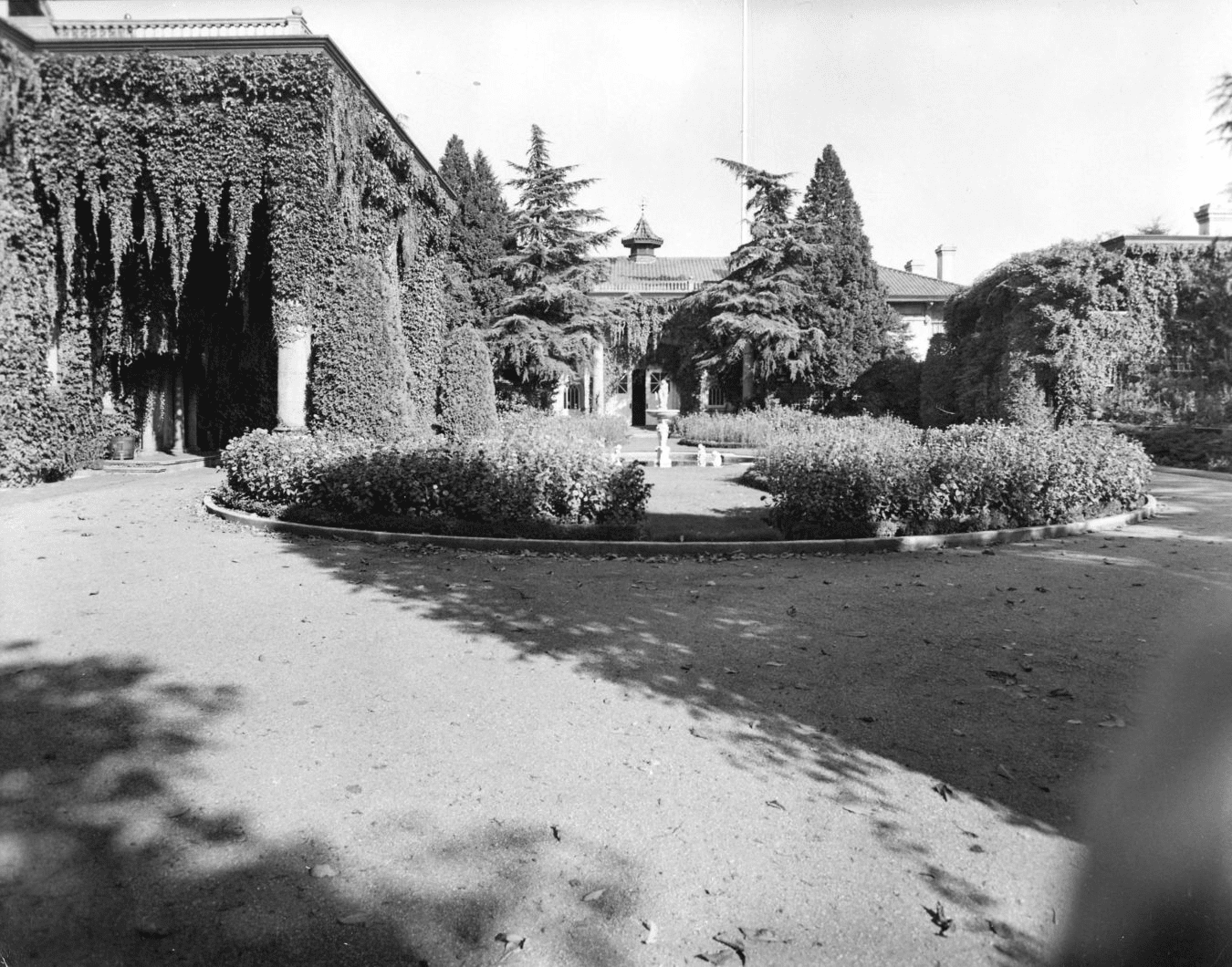

The facade boasts Edwardian elegance: symmetrical columns, balustrades, and tall arched windows. Inside, there are over 30 rooms, including a ballroom, a conservatory, and several fireplace lounges. Special attention was paid to marble, wood, and textiles. Materials were imported from Europe, with some elements custom-ordered from England. Everything had to meet the standards to which officers from imperial garrisons were accustomed. Construction was completed in 1911. Hycroft immediately became part of the landscape of Vancouver’s new aristocracy. It wasn’t just a house; it was a true demonstration that British Columbia had outgrown its colonial attire and was now donning a tuxedo. Indeed, this was where the first grand social receptions were held, where military club members gathered, and where business and political matters were discussed.

But beyond its external grandeur, Hycroft served another purpose. The residence embodied the “English dream” on Canadian soil. In this sense, Duncan’s home had no rivals, neither in scale nor in symbolic weight.

Hycroft as a Veterans Hospital

In 1924, following General Duncan’s death, his wife re-evaluated the mansion’s role. She donated the building to the federal government of Canada for the benefit of veterans. In essence, Hycroft ceased to exist as private property. Its corridors no longer echoed with officers in evening wear; instead, nurses, uniformed patients, and doctors now filled its spaces. The house began a new chapter. In the quiet of its spacious rooms, men returning from war found healing.

Individual rooms were converted into wards, beds were set up in the ballroom, and the conservatory became a rehabilitation area for physiotherapy. The courtyard, once adorned with coffee tables, now served as a space for patients to practice walking after injuries. This period lasted for nearly two decades.

It’s not often mentioned in guidebooks, but dozens of veterans from both World Wars underwent rehabilitation here. And while there were no drastic architectural changes, it was during this period that Hycroft shed its aura of an aristocratic, untouchable home. It became open—both literally and symbolically. It was no longer the estate of one general. It was a home for all those who had given a part of themselves on the front lines.

The Residence’s New Proprietors

In 1962, as the echoes of war had yet to fade from Hycroft Manor’s high ceilings, new residents arrived—intelligent, educated, and incredibly determined. It was then that the building was purchased by the University Women’s Club of Vancouver, an association of women with higher education dedicated to advancing science, culture, and social justice. Every room, every hallway became a space for discussions, public lectures, musical evenings, poetry readings, and seminars. The library, where the general once stored military maps, now hosted meetings with writers. The former ballroom saw classical music evenings and discussions on equality in access to education.

In 1974, the organization initiated a series of public talks on women in politics. Speakers included future federal Members of Parliament and community activists. It was from these conversations and panel discussions that new leaders emerged. Moreover, the UWCV began publishing its own materials, including brochures and analytical notes on women’s participation in science, public administration culture, and issues of access to financial independence.

Hycroft also became a platform—a space where educated women could freely express their opinions, discuss global events, and plan real change. Much of what official Vancouver history long overlooked took place here: intergenerational dialogues, support for young female students, and the city’s first feminist initiatives. Crucially, the club members meticulously preserved the mansion’s architectural heritage. They didn’t reconstruct the building beyond recognition but maintained its original appearance. Today, the UWCV boasts several hundred active members and continues to host events at Hycroft—from chamber music concerts to human rights forums. This is why everyone who steps into this residence feels that it is a place filled not only with the echoes of war but also with the memory of women who know how to change the course of history not with a sword, but with words, education, and dialogue.

Hycroft Manor Today: A Hub for Events, Stories, and New Beginnings

Today, the building belongs to the University Women’s Club of Vancouver, but it has long transcended the bounds of just a women’s club. It hosts lectures, charity galas, weddings, film shoots, and public events. As a result, Hycroft maintains a unique balance between preserving history and engaging in modern activities. Each year, dozens of private events take place here, including classic weddings with garden ceremonies, terrace receptions, and dancing beneath the chandeliers of the old ballroom. Among the particularly popular events is the annual Christmas at Hycroft, during which the estate transforms into a festive market with vintage decor, music, and artisan goods. This tradition has existed for over 40 years and is one of the most anticipated in the city.

Hycroft’s walls often serve as a film set. The Manor is easily recognizable in many TV series and films, including “The Killing,” “Arrow,” “The X-Files,” and even Netflix productions. Producers value the house’s interiors for their period atmosphere and aesthetic completeness. Despite being over a century old, the building’s infrastructure is maintained to a high standard: heating has been updated, electrical wiring modernized, and historical elements are restored according to the city’s heritage recommendations. According to the club’s administration, Hycroft is a living house that adapts to the needs of the modern community while remaining true to its history.

In 2023, Hycroft Manor hosted over 80 events, ranging from art exhibitions and chamber music concerts to professional conferences and charity galas. Membership in the University Women’s Club exceeds 400 women, including scientists, educators, entrepreneurs, and artists. At the same time, the house is open to the wider community: monthly open lectures are organized here on topics of history, science, gender equality, and urbanism. It is thanks to such activity that Hycroft has not become a mere museum—it remains a vibrant socio-cultural centre, deeply interwoven into the contemporary life of Vancouver.