At the very edge of Vancouver stands a remarkable building that holds the stories of people who lived here long before there were roads or skyscrapers. This is the Museum of Anthropology – a place not just to look at artifacts, but to feel the true roots of Vancouver. More at vancouver-future.

Origins of the Museum

The idea for the Museum of Anthropology (MOA) was born at the University of British Columbia in the early 20th century. At the time, scholars and explorers studying the coastal cultures realized the importance of preserving these artifacts. They collected them not for display, but to save the stories of the peoples who had lived here for thousands of years.

The first step came with the Frank Burnett Collection – a traveller who returned from the Pacific region with numerous household items, ornaments, wooden carvings, and masks. His gift became the foundation of the museum’s holdings. Soon after, UBC researchers joined the effort, bringing back new artifacts from expeditions across Canada and beyond.

The museum officially opened its doors to visitors in 1947. At first, it occupied just a few rooms within the main university building. As the collection grew, so did the need for a larger space – one that could house monumental totem poles, masks, and full-size Indigenous dwellings. In the 1960s and 70s, architect Arthur Erickson was invited to design the new building. A Vancouver native, Erickson understood the landscape deeply and wanted the structure to blend seamlessly with its natural surroundings. He envisioned a building made of glass, concrete, and wood – open to the sky and sea – that would extend the shoreline rather than interrupt it. His goal was not just to build a museum, but to create a place that felt part of the land itself.

Architecture

The Museum of Anthropology doesn’t look like a typical museum. Erickson designed it to let natural light flood through its glass walls, while the concrete and wood merge with the earth around it. On sunny days, the space glows softly; when it rains, the surfaces reflect the sky. Visitors often describe the feeling as being sheltered by a transparent canopy in the middle of the forest.

The architect drew inspiration from the traditional “big houses” of the Northwest Coast First Nations. Their design is simple yet majestic – massive wooden beams, open interiors, and the scent of cedar that evokes the spirit of ancient villages. Rather than replicating these structures, Erickson reimagined them for the modern era.

From the museum’s windows, visitors can see the ocean and mountains. It’s more than a beautiful view – it’s a reminder of where the stories of these lands and peoples began.

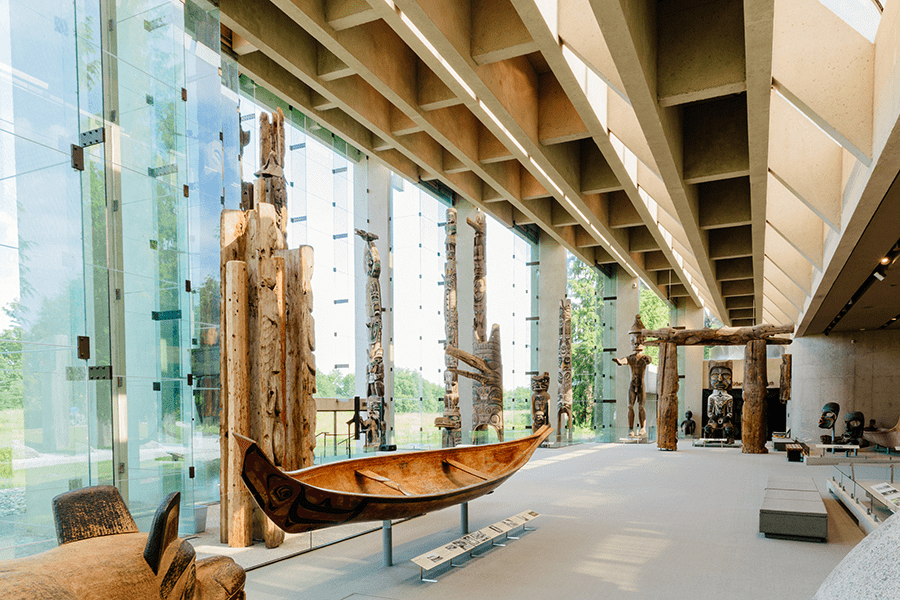

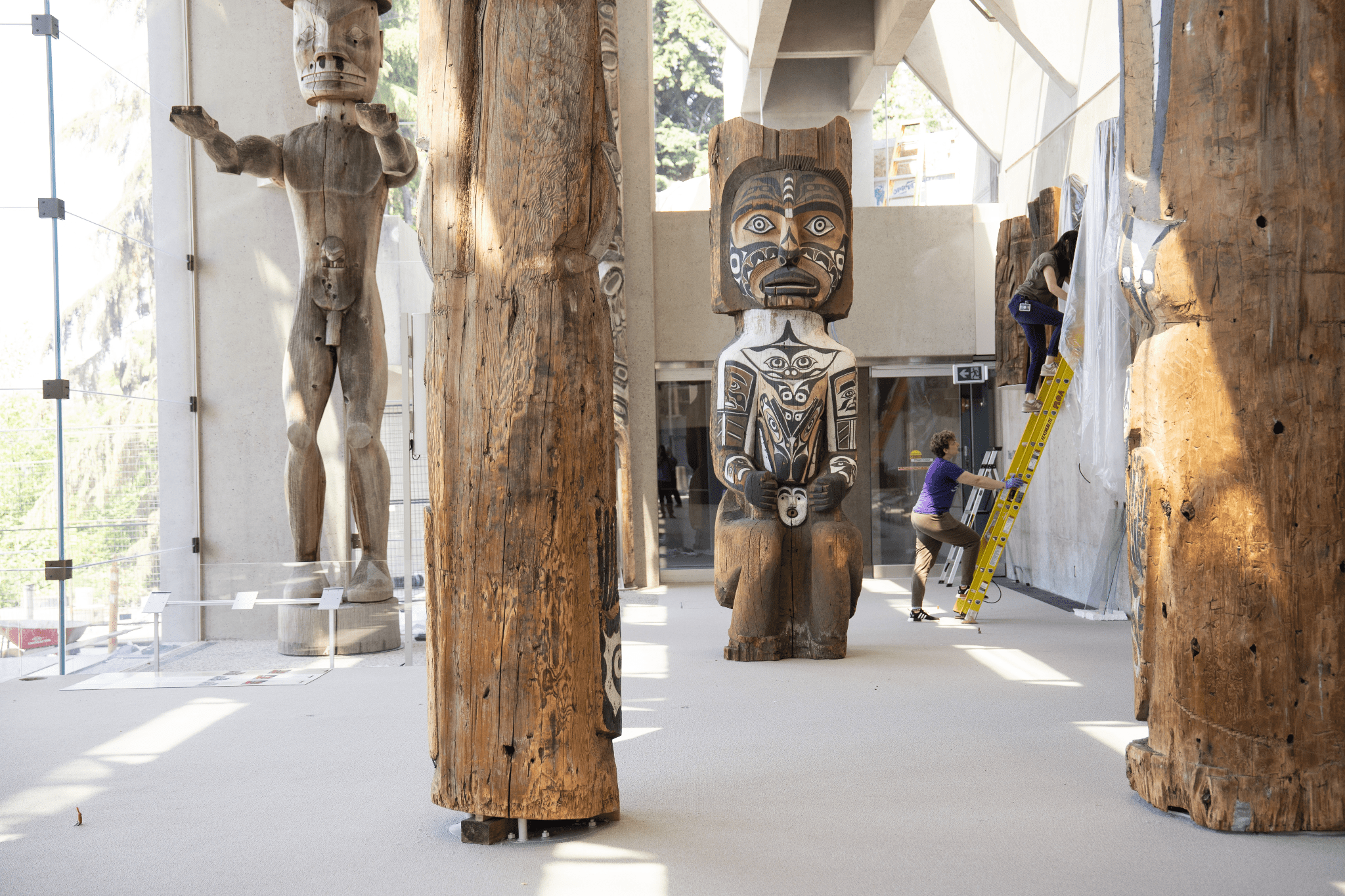

Standing in the Great Hall among the towering totem poles, the air feels thicker. The space seems to slow time itself. Conversations drop to a whisper, and even children stop running – as if instinctively aware of the sacred weight of the place.

Collections and Exhibits

Inside the museum, the Great Hall houses massive totem poles, carved figures, canoes, and house posts from the Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Coast Salish peoples – nations who lived along this coast long before European arrival. Each object tells a story, carved from cedar or shaped from stone. Nothing here was made merely for beauty; every piece once held a role in songs, ceremonies, and family histories.

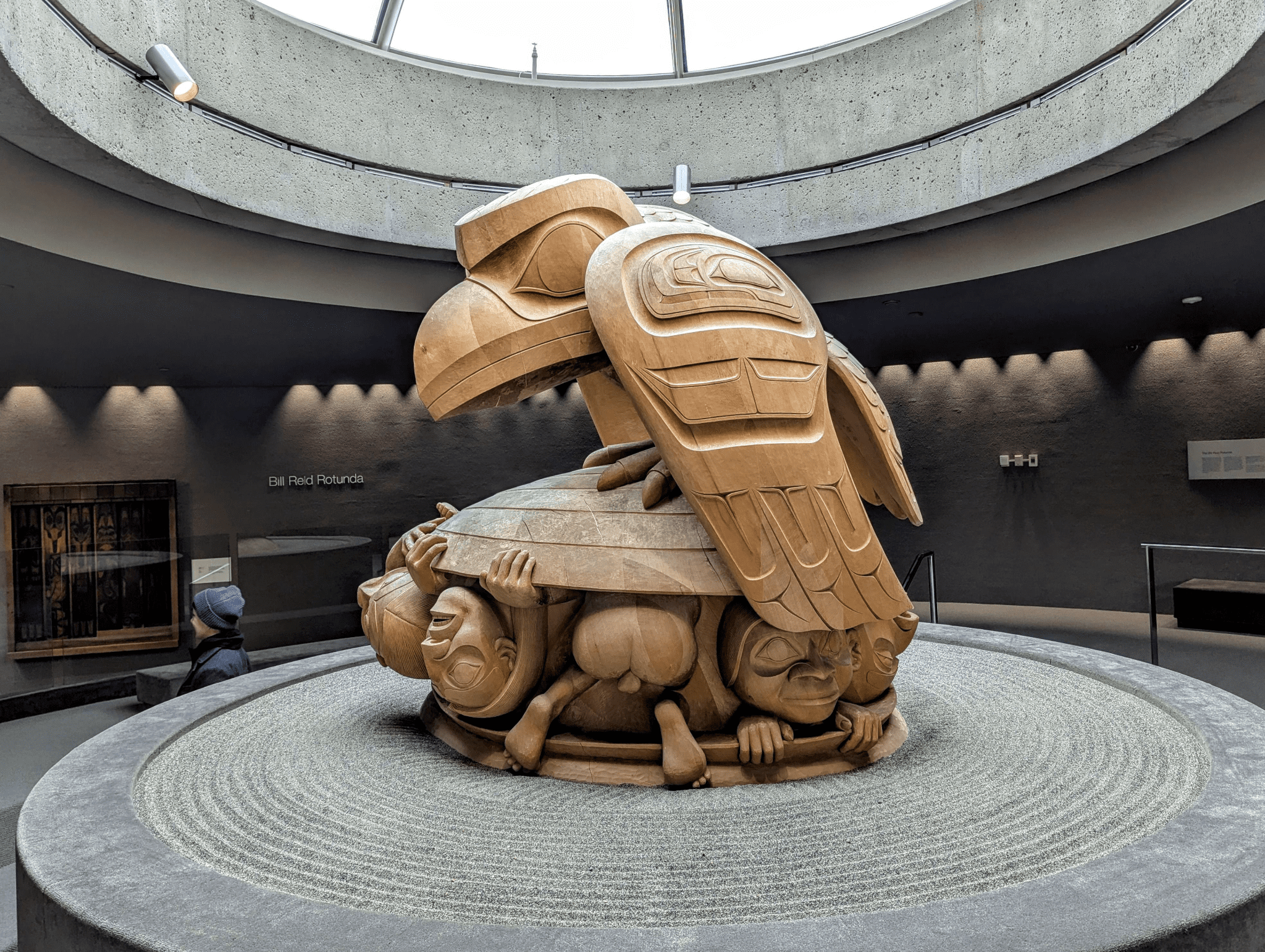

Among all the treasures, one work has become the museum’s defining symbol – Bill Reid’s The Raven and the First Men. The sculpture depicts a raven opening a clam shell to release the first humans. Reid, a Haida artist, helped bring the imagery of his ancestors back into contemporary culture.

Beyond the Great Hall lie the Multiversity Galleries, an expansive space holding more than 10,000 objects from around the world. Displayed in simple glass cases, they invite close encounters – carved masks, woven textiles, ceramics, and adornments. Each label tells a brief story, a glimpse into someone’s life across time and distance.

Another highlight is the Koerner Ceramics Gallery, where bright white light and neatly arranged shelves display hundreds of ceramic pieces from different eras and regions – from ancient bowls to modern sculptures.

The museum is constantly evolving. Temporary exhibits bring in artists from around the world, showing how ancient traditions find new life in modern art. Today, many displays include multimedia and interactive elements: visitors can watch archival footage, listen to old songs, or explore digital archives to uncover the story behind each artifact.

The Spirit of Heritage

From its earliest days, MOA has aimed to work with Indigenous communities, not just about them. Every exhibit and artifact represents a living culture, and the museum treats them with deep respect. Many curatorial decisions are made collaboratively with the Haida, Musqueam, Kwakwaka’wakw, Coast Salish, and other Nations. This approach, known as shared authority, is built on mutual responsibility for cultural memory. It’s more than a principle – it’s a way to rebuild trust after a history of items being taken without consent.

Today, some artifacts are being returned to their home communities. The process is complex and requires cooperation, but it carries great meaning. Some items remain on display under agreements with their Nations, ensuring that each object is treated with respect and understanding of its spirit and story.

Beyond exhibitions, MOA runs numerous educational programs. School groups, university students, and young researchers often visit to learn directly from Elders. Teachers and artists also take part in programs that help deepen their understanding of the region’s diverse and layered histories.

Through these initiatives, the museum encourages visitors to view Canadian history not as a linear timeline, but as a mosaic of perspectives, traditions, and voices. For many, encountering these stories becomes a moment of reflection – a recognition that behind every mask, song, or carving lies the enduring memory of human experience.

The Museum Today

In 2024, the Museum of Anthropology underwent a major renovation and seismic upgrade. The renewed building, reopened after 18 months of work, feels brighter, safer, and more welcoming.

Today, the museum serves as a living cultural laboratory. New exhibitions open regularly, and digital archives and multimedia installations continue to grow. Visitors can not only see historic totem poles but also hear traditional songs, engage with interactive activities, and follow guided paths revealing deeper layers of meaning. Each gallery carries its own atmosphere and sense of authenticity that captivates everyone who walks through.

The Museum of Anthropology now stands as both a local and international cultural hub, attracting artists, scholars, and students from around the world eager to explore the living traditions of Indigenous peoples and their contemporary expressions.

For everyday visitors, it remains a profoundly special place. Every sculpture, mask, and ceramic piece invites reflection – a quiet connection to the living memory of this land.

Sources:

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG121763

- https://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/burnett_collection.pdf

- https://moa.ubc.ca/about-moa

- https://visit.ubc.ca/see-and-do/museums-and-art-galleries/museum-of-anthropology

- https://260erickson.wordpress.com/works-and-achievements/museum-of-anthropology